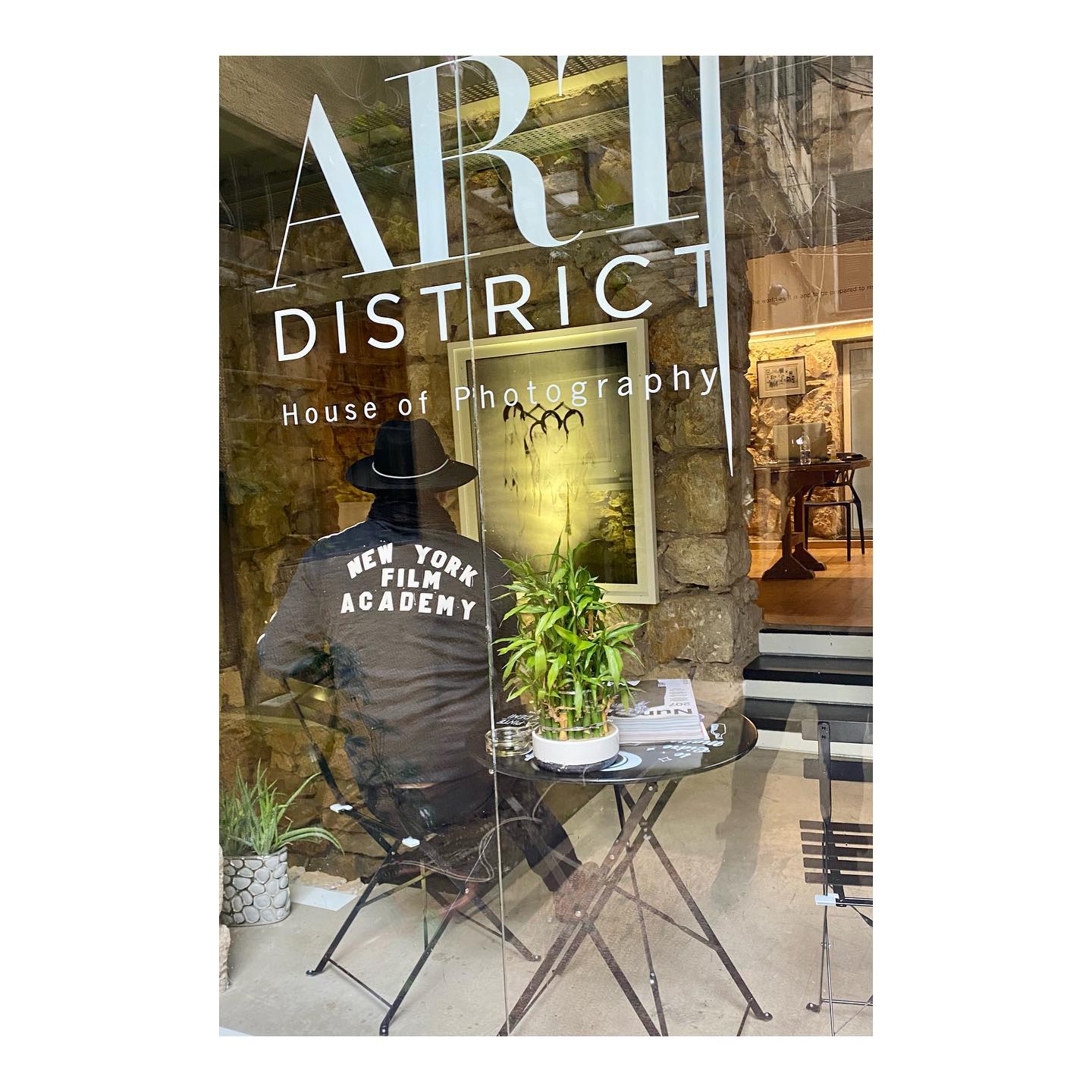

After a long international career, Maher Attar turns to art and beauty at Beirut’s Art District, aka L’Atelier, the gallery he opened in the aftermath of the August 4, 2020 explosion, in the emblematic Gemmayze district, where he promotes a new generation of Lebanese photographers and artists.

Nicole Hamouche

Amidst a host of crises and disasters, what remains for young Lebanese is art, and in particular photography — the art of “painting with light” as a way to sublimate the literal darkness of a daily life often devoid of electricity. As the great poetess of this Lebanese land of fire and light, Nadia Tuéni puts it, “art […], when it comes to authentic creators, is above all the confrontation with one’s destiny.”

Art and photography in Lebanon found a new home in the creation of Beirut’s Art District, one year after the explosion in the port. Maher Attar, a former photojournalist of international renown, wanted to support emerging Lebanese photographers and artists and provide them with a space to exhibit their work. Beginning with the Lebanese civil war, Attar has covered many of the conflicts in the region over the last decades — right up to the war in Afghanistan. In 2016, he returned home, having decided that he would devote himself mainly to fine art photography, as well as to promoting emerging Lebanese talent.

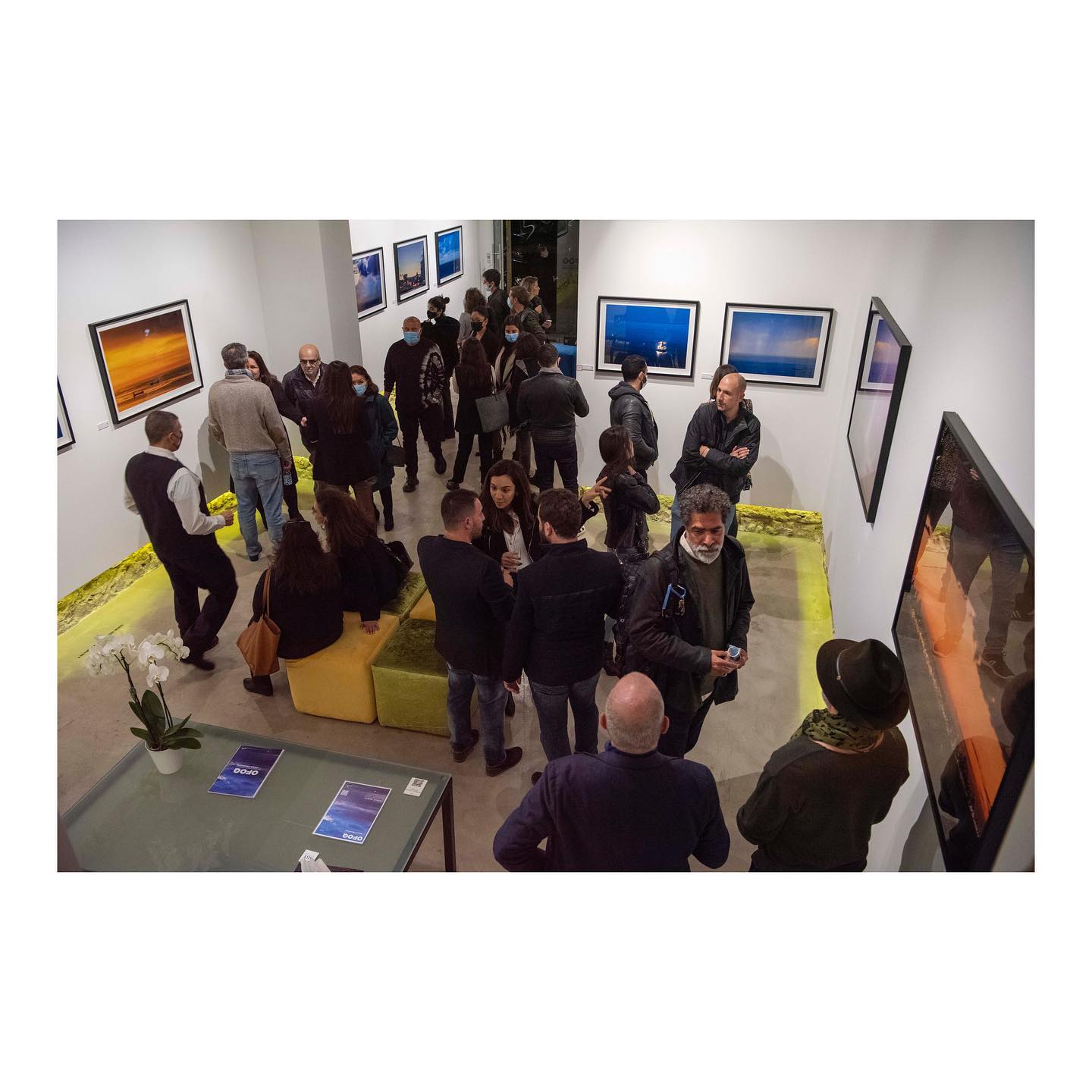

But by 2020, deep into the economic crisis and in the aftermath of the devastating port blast on August 4th, he was at the point where he was questioning whether to remain in Lebanon or return to France, the country where he’d advanced his career and to which he remains strongly connected. Then one day, while on a walk in a Beirut still bleeding from the wounds of the explosion, the photographer came upon a building that caught his attention. Right there on Gemmayzé Street — in a landmark neighborhood of traditional Lebanese architecture bearing scars of the port blast — he happened upon a space perfectly suited to host his dream project. He contacted the owner, who agreed to rent it to him with easy payment terms. Attar rehabilitated it, and within a month, the gallery was up and running, with the mission of being an incubator of talent.

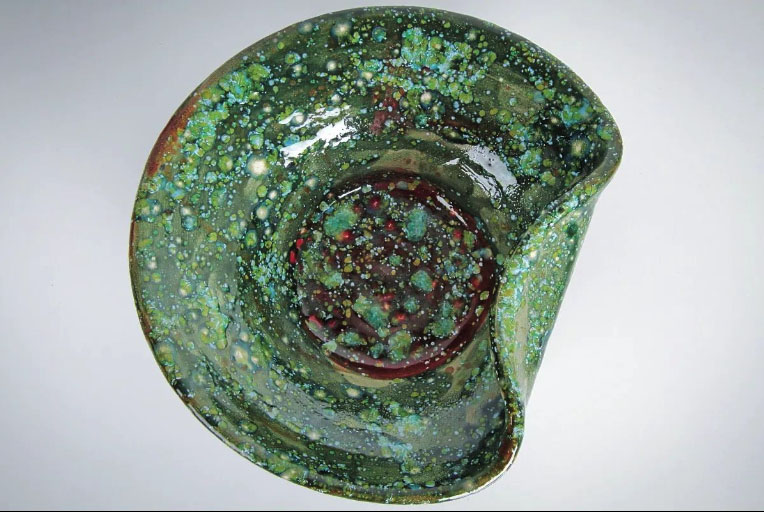

This space, with its ancient stonework, high ceilings and quiet atmosphere is the perfect embodiment of the essence of Beirut Square, a rare platform for expression and diversity in the Arab world. By offering an exhibition space, Maher Attar hopes to encourage Lebanese photographers to embrace their visions and express themselves — even in politically incorrect ways — which is especially important in a country where freedom is increasingly compromised. The works of Lebanese artists rub shoulders with those of their Syrian, Iraqi, Qatari and Jordanian peers, who each have something unique to say about the status quo in their countries, as well as about life and freedom more broadly, many of them having lived in different countries around the Arab and larger world. The artists exhibited in Attar’s gallery include photographers as well as sculptors, such as the Syrian Badie Jahjah with his whirling dervishes; the Iraqi Rim Al Bahrani with her buildings; Lina Lotfi, a Lebanese living in Qatar; and Myrna Maalouf with her busts of women — dedicated to women with breast cancer. The latter’s works were targeted by religious extremists when they were exhibited in a public square as part of an awareness-raising campaign. But Attar is no stranger to championing social causes, having seen and experienced war and its madness up close. From such a point of view, art can only be engagé or political, even in its discretion and silent elegance.

The gallery opened with the first solo exhibition of Maher Attar’s work. For the occasion, the gallery floor sprinkled with quotations addressed to visitors: a gesture of tenderness extended to those still reeling from the shock of August 4th against a backdrop of abysmal crisis. Attar hung a sign in English on the wall, in large type: “Accepting what is and rising above it.” It acts as a sort of epitaph, inviting visitors to bury violence and resentment and open up a wider space of expression and possibility.

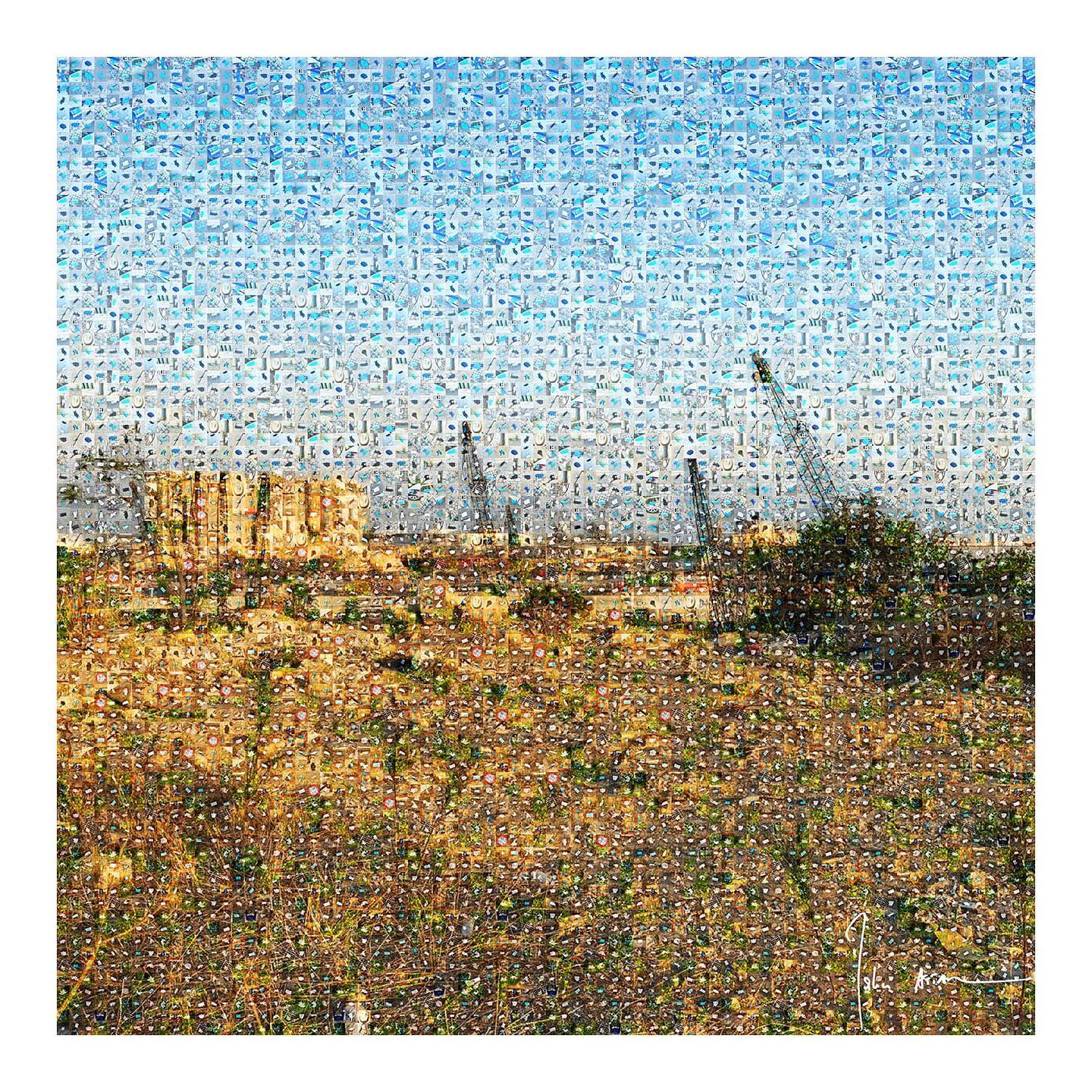

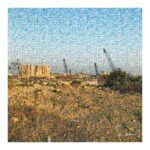

Attar’s photos document a period of confinement he spent out in nature — the best of confinements. Before that period and even before the October 2019 revolution, Maher Attar had assigned himself an artistic project he calls “Berytus, a glorified city” — a title referring to the Beirut of Roman times, when the city was an emblem of the rule of law and respect for the humanities, this in total opposition to its current status. With his loving eye, he wanted to give vitality back to his troubled city, reminding viewers of how beautiful and fertile it had once been. “I wanted to restore Beirut to its former glory,” he explains. “At one time, it was a glorious city, under the Romans. It was highly regarded then.” In a theatrical setting, he depicted the city as a woman who has taken a lot of hard knocks but still holds on. His Lebanese Marianne conveys a message of dignity, freedom, peace and diversity: everything that Berytus may have symbolized at one time or another. Then came Lebanon’s rapid decline, and the artist was no longer able to take his project to the international stage as he had hoped. The idea is now back on his mind — all the more so as 2025 will mark the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the start of the Lebanese war.

Although Attar’s homeland occupies his heart, his interests and his subject matter go far beyond its borders. And he has shared some of these works with his Lebanese audience. For example, his One Year of Happiness, an older, quite Parisian exhibition of his backstage photos of the Paris Lido, where feathers, femininity and nude curves serve as expressions and celebrations of joy. He has also exhibited photos from the collection of Dominique Aubert, a former colleague from the Sygma agency, who offered them as a gesture of support for the new gallery: photos of aviators and race car drivers that tell of a time when men knew how to dream of freedom and live it. Alongside these one-off exhibitions, the Art District is also home to talented young Lebanese artists such as Elie El Khoury, photographer and master printer Khodr Cherri, Dana Mortada, Chloé Khoury, Luna Salem (and a growing number of other women besides), as well as architects. Together they provide a glimpse of a liberated and ambitious art scene, with equal photos depicting the direct social environment in Lebanon as from the farther-flung corners of the world.

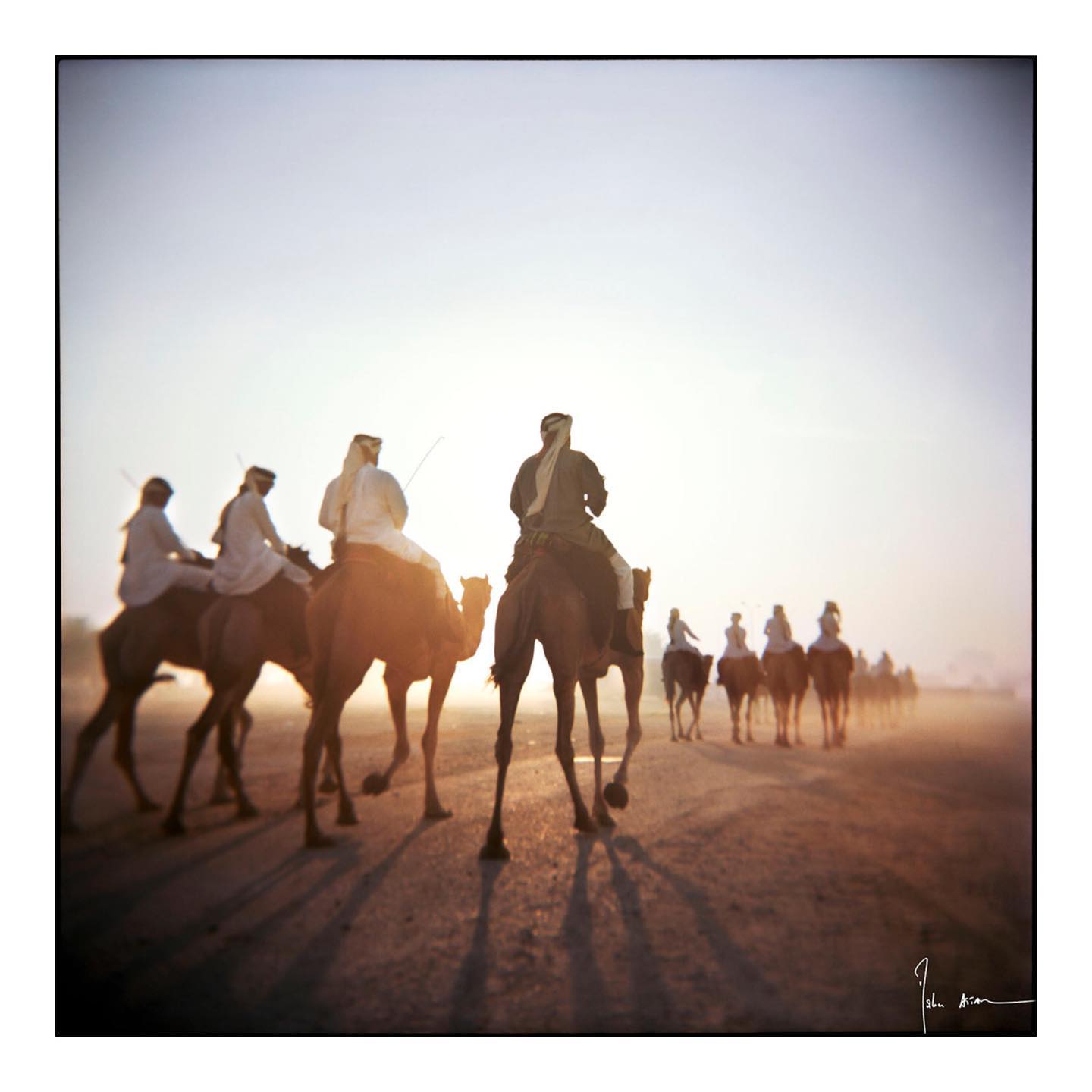

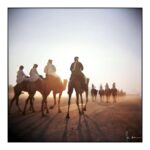

The strength of these photographers lies in their ability to be patient, even in times of urgency and crisis, waiting for the right angle of light that will allow them to capture the decisive image. And Attar’s strength specifically is the way he explores a different relationship to time than that of the fast-paced digital age, by working with lomography, a technique that uses silver film and is based on spontaneity and the rejection of photographic canons, and where, unlike digital photography, you can’t really control the result. “Photographing with expired film makes you realize that you have to trust yourself and your camera more,” says Attar. And so when selecting artists for exhibition, he does not retain those who take their images on smartphones, even if it’s the current trend. Thus, Attar dares to be of his time while not being of it.

Attar’s mission as an artist and now curator is informed by a deep sense of responsibility. In his time as a war photographer, he witnessed chaos from all sides: militiamen firing on the Lebanese army, other militiamen waging war in the Palestinian camps. He had seen what war does to children and the way it deprives them of schooling. Having also had to interrupt his own education due to war, it’s a cause to which he’s particularly sensitive. Therefore, for instnace, under the framework of the Qatar foundation’s “Education Above All,” he conceived and carried out the “Challenges and Realities” series, to advocate for the cause of out-of-school children. His reporting took him to 11 countries, including Haiti, Thailand, Pakistan, Sudan, and Kenya, and culminated in a book of photos as well as exhibitions at the UN headquarters in New York and then at UNESCO in Paris. In 2009, he also ran workshops with children in Nepal, Cambodia and Indonesia, helping them to see things differently, that is, through the lens of a camera. Upon departure, he left the cameras behind with them, and Attar still remembers how some of them wept with joy to receive the gift.

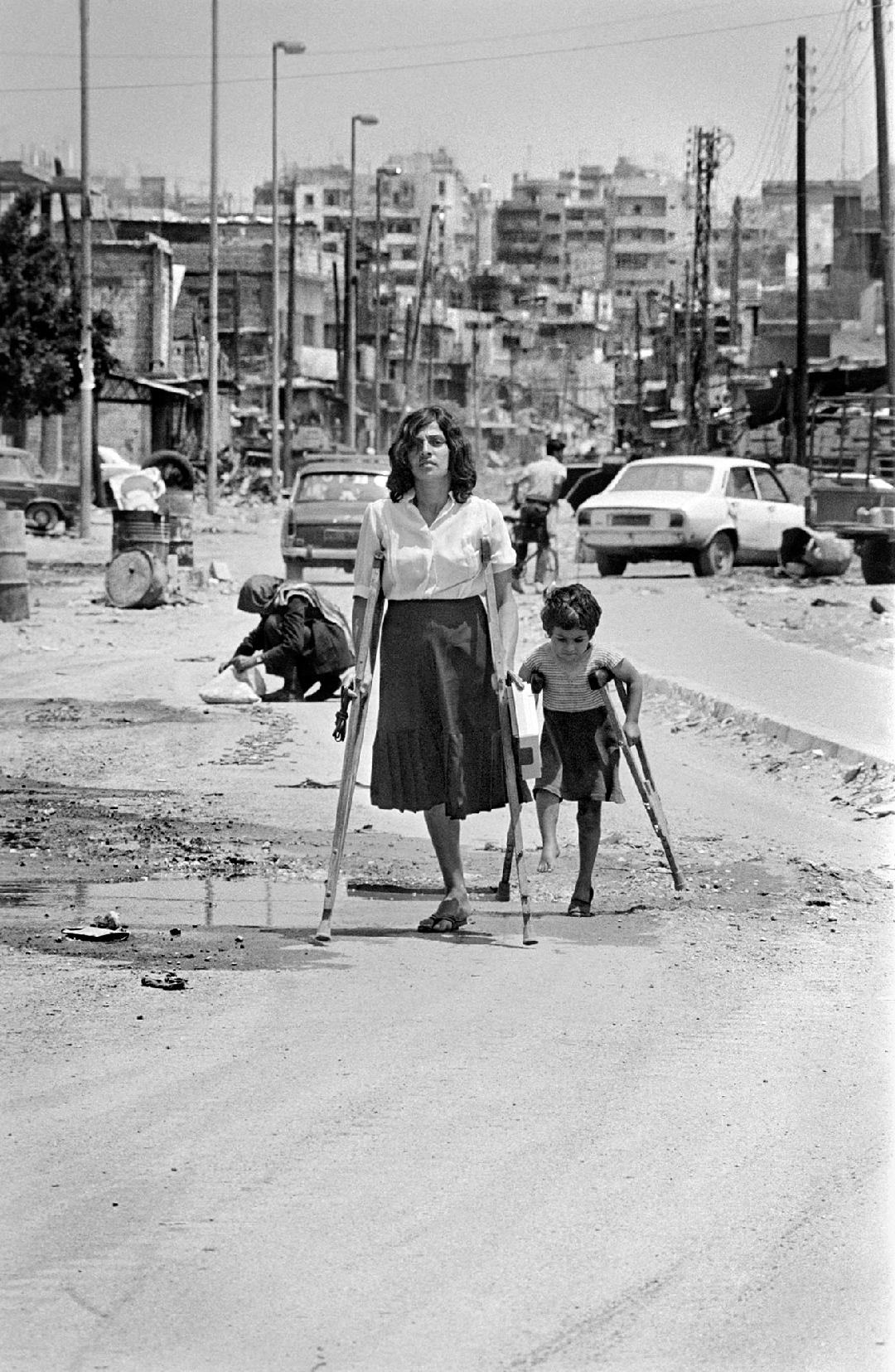

Today, the man who ran after a scoop at the age of 20, hoping to sell an image to AFP or another international agency in order to make a name for himself, claims that “risking your life for a scoop [isn’t] worth it.” He knows this from personal experience: he was seriously wounded twice in the heat of battle. The first time a bullet passed through his face and he fell from the second floor to the ground and into a coma. The second time, a bullet exploded in his leg and caused a serious infection. He spent eight months in the hospital and his leg was nearly amputated. But he was young at the time and ferociously ambitious. He wasn’t shy about mingling with the legendary reporters who frequented the Commodore Hotel bar during the days of the war — reporters such as Eddie Adams, who had come to cover the Israeli invasion of Beirut after having covered Vietnam. Their example stimulated and empowered him to move forward and reach for greater heights. Then, in June 1985, during the war in the Palestinian camps — which pitted the Amal party against the Palestinians — he captured a photo that made the front page of the New York Times and immediately launched his international career. On the back of it he spent 17 years with the Paris-based Sygma agency, criss-crossing the globe.

Paradoxically, though it was violence that first brought him to the art of photography, what Attar is most interested in capturing is tenderness. “There’s a tender violence in my images,” he says. “I’ve always sought tenderness. That’s what I wanted to document in my photos.” For after all, tenderness is light, and light is tenderness. Will he still be able to find it in Beirut, which the poetess Nadia Tuéni once characterized as “the last sanctuary in the East where man can dress in light?”