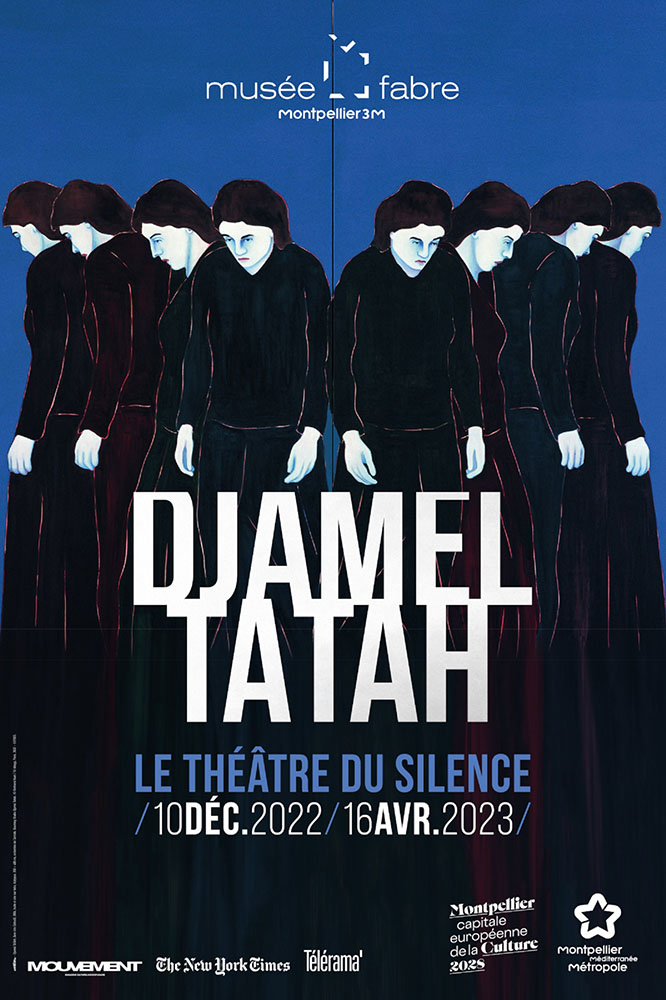

The French-Algerian artist Djamel Tatah (b. Saint-Chamond, 1959) unveiled his exhibition “The Theatre of Silence,” on view at the Musée Fabre in Montpellier through April 16, 2023.

Laëtitia Soula

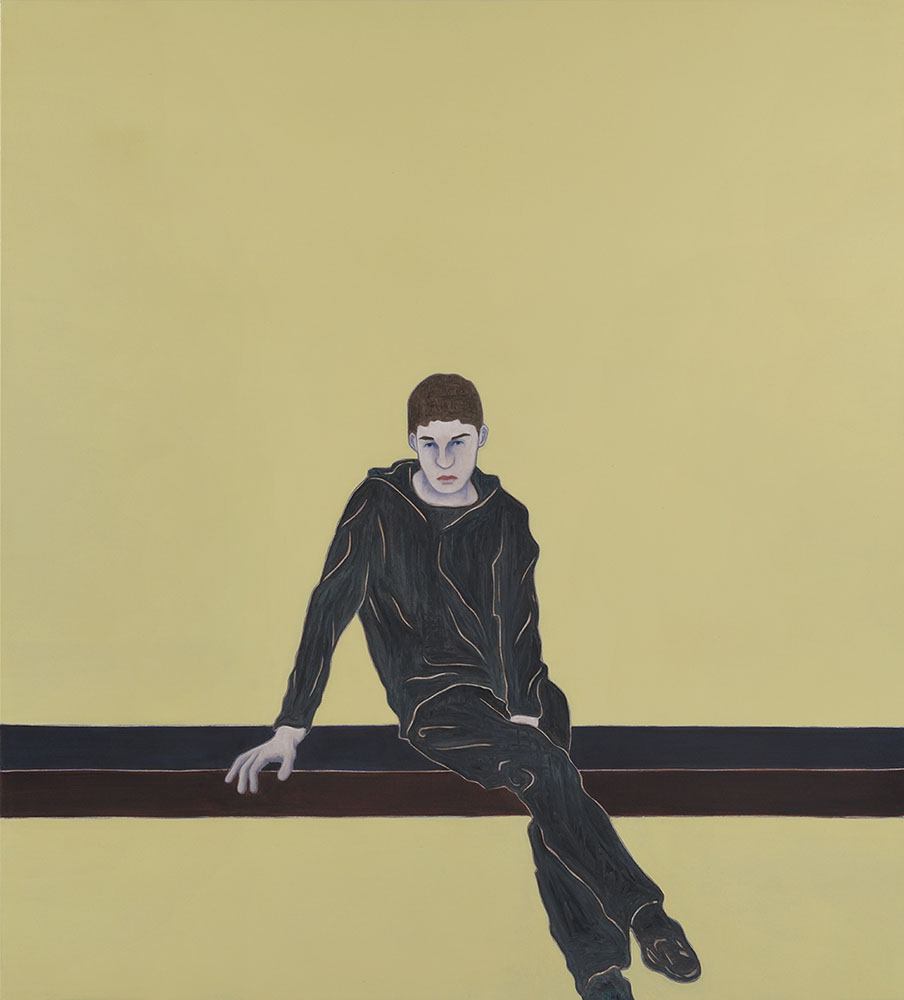

In December, taking inspiration from the Theatre of the Absurd and the study of crowds, Djamel Tatah, a resident artist in Montpellier since 2019, unveiled his vast exhibition “The Theatre of Silence” at the Musée Fabre, where the viewer discovers both crowd paintings and isolated human figures, surrounded by large flat areas of color. The bodies are standing, sitting, on the ground, stretched out or suspended. One can see the wavering and the loss of balance, a sober gesture of the bodies, faces without expression. The format is monumental. The show is a tour de force, as his large canvases convey powerful emotion and cause one to reflect on man and the human condition.

The humanity that surrounds us

Trained at the Beaux-Arts de Saint-Etienne where he discovered figurative painting, Tatah has built a body of work over more than three decades that questions our presence in the world, and the empathetic relationship to the humanity that surrounds us. He draws inspiration from Samuel Beckett’s plays such as Waiting for Godot and Endgame, as well as Albert Camus’ classic work, The Myth of Sisyphus, quoting the latter: “Man stands face to face with the irrational. He feels within himself his longing for happiness and for reason. The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world.”

In an interview with the exhibition’s curator, Michel Hilaire (published in the bilingual catalogue Djamel Tatah, Le Théâtre du Silence), Tatah said that as a result of his Algerian immigrant parents, “I’m a child of the colonies” and “I was born and raised in France in the context of a proletarian culture where Sicilians, Armenians, Spaniards, Turks, North Africans, Auvergnese, etc. lived together.”

The artist first visited Algeria as an adolescent and returned there several times in his early 20s. It was when he visited the Roman ruins of Tipaza in 1982 and came across a stele that he discovered Albert Camus, who remains for many Algerians a controversial and often divisive figure, mainly because of his position on France’s colonial relationship with the country that fought and won its independence in 1962.

Having grown up in a diverse environment that included other immigrant families stoked Tatah’s sense of the underdog. He explained to TMR, “I have a real love for Basquiat and I was very early interested in the rights of black Americans early on.”

The work of the American painter Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) is notable for its pioneering role in pop avant-garde and the underground movement. Tatah’s work also bears the influence of German Expressionism and the visitor will be able to find references to Eugène Delacroix, Edouard Manet, the photographer Eadweard Muybridge and the Italian Renaissance painter Antonello de Messina.

In the course of walking amongst Tatah’s paintings, one will find more than one reference to Camus. A militant journalist and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957, Camus defended the rights of the people of North Africa against colonization, but struggled with a conflicted relationship between his adoptive and colonizing nation of France with his native Algeria. In his work, Camus questions the absurdity of the human condition, and the revolt that gives meaning to the world and to existence.

Initiatory journeys and aesthetic shock

As for Tatah now, he explains, “My work reflects hybridization and modernity…I remember my trips to Algeria when I was young. I accompanied my mother to the village, and then I went hitchhiking around Algeria. These were real initiatory trips, because I wanted to know the country where my parents came from.” Tatah says that he experienced a real “aesthetic shock” in Tipasa, a coastal Algerian city with numerous vestiges and monuments such as the Royal Mausoleum of Mauritania.

We can find in Tatah’s painting architectural elements from Algerian Islamic art, such as column patterns, from the ruins of the mosque and palace of Mansoura in Tlemcen. The artist questions the passage of time that leads to ruin, introduces elements of ancient sculpture, and renders remnants that represent our inevitable disappearance.

The visitor can also see the influence of Byzantine icons, with illustrated figures on colored flat tints, as well as motifs from Persian, Indian or Arabic illuminations. Men with closed eyes, lying bodies, silent mourners represent ensoulment or death.

“My love for art history has never been compartmentalized, and hybridization is very important to me, in relation to my culture, my origins,” explains the artist. “I developed my own laboratory to mix images and techniques. I worked a lot from photos, because I like to put the subject at a distance, and to set up a scene, like in the theatre. I also draw on the computer to make a video-projection on canvas, and I sometimes had to take up technical challenges, for example when I had to paint on huge fabrics to make the flying figures.”

Suspended time and Algeria’s “Black Decade”

Tatah stages “time stopped, suspended, to create tension,” he says, sometimes drawing inspiration from the choreographic movements of dancers. Is it a fall or an elevation? Whether it is physical, social or spiritual, it leads to the inexorable disappearance of human beings.

We can thus admire imprisoned characters, anonymous crowds, flying figures — a loneliness pegged to the body, and faces without expression which seem to bear witness, but to what? In fact, almost all the pieces in this exhibition remain untitled, as if they speak anonymously.

“Femmes d’Algier,” a painting created in the 1990s, echoes the civil war that tore Algeria apart during the period known as the Black Decade. This long conflict between the government and Islamist groups resulted in the deaths of nearly 150,000 people, thousands of missing persons and the exile of populations seeking to flee the terror. Tatah decided to paint anonymous, passive and silent women. They call out to whoever crosses their eyes, while the tragedy unfolds.

Another figure to whom Tatah pays tribute is the late Franco-Algerian singer Rachid Taha, who died in 2018, and who also practiced hybridization, not in painting but in music, skillfully mixing rai, chaâbi, techno, rock and punk. With his group Carte de Séjour, Rachid Taha was the voice of proletarians who tell the stories of immigrants, at the time of the great March for equality and against racism, from Marseille to Paris.

“We were friends for nearly forty years,” says Tatah now. “We followed a long common path, which has been fraternal. We have exchanged a lot. Painting his portrait, I wanted him to be with me always.”

Relationship to the world and political position

“The main idea of this exhibition is that of presence and our relationship to the world,” Tatah says. He confronts us with the pure presence of bodies that call out to us. The works cry out this incommunicability of beings that cannot meet. The solitary crowds, the ancient choirs of women, the repeated figures, seem universal, and the way in which art can embody the world, in the image of the Greek myth of the sculptor Pygmalion in love with his creation, Galatea, a statue brought alive thanks to the goddess of love Aphrodite.

Tatah tries to “find a form of universality in the pictorial language, beyond our origins,” taking as an example the Hittites (from the word “hit” which means “wall” in Arabic), young men from the French and Algerian suburbs who spend their day idle, leaning against the city walls. Heads down, hands in pockets, they compose a frieze of figures repeated dozens of times across a set of canvases. Their fate is multiplied as Tatah makes them visible: “My history comes from immigration and the proletariat from which my parents come,” he explains. “I wanted to pay tribute to Algerian youth and the tragedy that is theirs, like the Intifada in Palestine.”

It’s clear now why Tatah exults in repetition of form and thought, to confront racism, war and oppression, repetition to exacerbate and accentuate the idea, the feeling, as if to illustrate what the core character of life, a subtle stripping down to represent Man in a universal way. His figures exude a powerful presence that shakes the viewer to our core.

“My painting is silent,” concludes the artist. Imposing silence in the face of the noise of the world is in a way adopting a political position. It encourages us to step back and carefully observe our relationship to others and to society.