To commemorate annual recognition of the Armenian Genocide on April 24th, TMR is publishing two columns, Heritage by Aram Saroyan and Armenian Eyes by Mischa Geracoulis, each of which takes the reader back through personal memories of family and belonging, in the Armenian and American diaspora. See also our Resource Guide to Armenian Culture for a recommended list of writers, artists, filmmakers and more. —Editor

Mischa Geracoulis

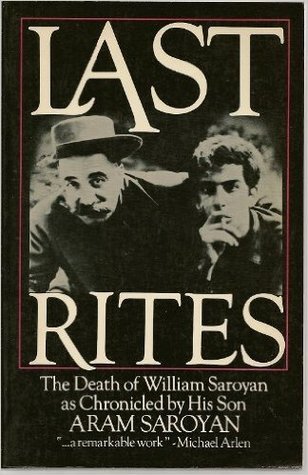

Though it had been on my reading list for years, I’d held off entering into Aram Saroyan’s Last Rites: The Death of William Saroyan (William Morrow & Co. 1982) until recently. Facing his account of the last months, weeks, and days of the life of his legendary father, William Saroyan (1908-1981), would be something of an homage to my grandfather, Levon Stepanian (1910-2003). Having all but single-handedly created the American multi-ethnic literary genre, William Saroyan is renowned among Armenians and non-Armenians alike. He paved the way for the rest of us, not the least of whom is his son, Aram Saroyan, prolific writer, poet, and artist of his own making and fame.

Springtime, Great Lent in the Christian calendar, and the lead-up to the annual April 24th Armenian Genocide commemoration is a period that lends itself towards reflection. That my grandfather made his transition one April, and that Last Rites takes place during another April, signaled that this would be the April to read the book.

For about 24 hours after finishing Last Rites, I was in such a weird space — relating to the push-pull emotion, family drama, and generational trauma, “something unnamed in the pit of the stomach,” as Aram describes it — that I reached out to him. It had been at least 10 years since our last communication.

Over email as we reconnected, I reminded Aram of the time that my grandfather Levon had hosted his father in Philadelphia in the 1930s. With an American public school eighth grade education under his belt, at age 14, Levon embarked upon a speaking circuit with the Rotary Club, an international humanitarian organization that promotes peace, good will, and social justice. He travelled by bus, and depending on where he was in the U.S., determined which section of the bus he rode. Often, it was in the back. Upon arriving in a new city, Levon did what his father before him had done upon arriving fresh off the boat in New York. He went to the phone directory and searched for Armenian surnames. Levon’s mantra, “Armenian people, good people,” instilled in him by his mother, emboldened his search for lodgings with Armenian families.

By the mid-1930s, Levon was gaining momentum as a popular speaker. William, meanwhile, having had one or two books published by that stage, was enjoying significant notoriety. It was around this time that Levon hosted William Saroyan at the Rotary Club of Philadelphia, who, as the story goes, spoke to a packed house of enthralled attendees. Afterwards, the Rotarians entrusted William to Levon for a night on the town. 1930s Philly was an epicenter of creativity — from Art Deco to jazz and speakeasies to cuisine and mercantilism of myriad sorts. Recalling old photos of Levon and William, it’s easy to speculate that the two twenty-something Armenian bachelors cut debonair figures in Italian pinstripes and fedoras as they stepped out into the evening. Apparently wanting to impress, Levon took William to dinner at a Chinese restaurant. Though my grandfather’s rendition was scant of much further detail, the implication was that the goal was succeeded.

In 1997, I was in Yerevan, which coincided with the grand opening of the first-ever Chinese restaurant in Armenia. A friend and I went for dinner and witnessed an awkward clash of cultural palates: Armenians, new to Chinese cuisine, were distressed by the absence of lavash. Unfamiliar with the Armenian staple, the Chinese restaurant’s opening night success was blunted by unmet customer demands for the ethnic flatbread. I later heard that as a matter of basic survivability, the Chinese restaurant added lavash to their menu.

Imagining the conversations that my grandfather and William might have had in the Chinese restaurant in 1930s Philly, I asked over email, “Aram, do you think those two Armenians expected lavash with their Chinese dinner?” Doubtful. Unlike the Armenians of post-Soviet Armenia, the Armenians of Levantine Turkey were quite cosmopolitan; until the Ottomans. As Elia Kazan explains in his film America America, Ottoman rule rendered the Greeks and Armenians subservient, second-class citizens.

William’s and Levon’s families had similar trajectories, zigzagging west, east, west. Their fathers were worldly polyglots, coexisting pluralistically long before “coexist” would become a trendy bumpersticker; until the Ottomans. Far from Fresno, California, far from Smyrna, thinking of those two sons of Anatolia having dinner at a Chinese restaurant in Philadelphia in the 1930s, I am awed by the connections that have wound their way down through the generations. Aram and I marvel at their bravery, and that of their generation. Recalling the opening scenes from Kazan’s America America, with Mount Ararat, symbol of freedom, in view, Kazan proclaims that he’s Greek by blood, Turk by birth, and American because an uncle made the journey. Crossing oceans on steamliners, crammed into steerage, determined not just to survive, but to thrive, they were all brave.

My grandfather confided stories in me that bypassed his own children. When I was little, he’d take me to visit relatives and friends from the Old Country. Old Man Krikor was from “our tribe,” and spoke no English. I was probably four years old, and though I don’t have many memories from childhood, I remember vividly this one visit in particular. A man of few words, Old Man Krikor stared at me intently as I squirmed in my chair. He eventually spoke. Holding my hand, my grandfather translated. “He says you’ve got Armenian eyes. And Armenian blood. He says not to let you forget.” There was something about the way they both looked at me, looked into me, that imparted a sense of import. I didn’t quite understand, but I sat up a little taller.

As Levon’s firstborn grandchild, the torch was passed, and internalized. Internalized too would be the syncopations of an ancient language, music, and dance, the mystical chants of the Armenian Orthodox church, the intergenerational trauma of Genocide, and duty towards its recognition. Of course, I wouldn’t become cognizant of any of this until much later.

Not unlike William Saroyan, my grandfather Levon had a larger-than-life persona, and a temperament that could swing high and low. In the sourest of times, my mother referred to the family as “screamin’ Armenians.” And in the best of times, Levon was a showboat who loved to joke and tease. At family gatherings, an old standard was his version of Marlon Brando: Ste-lla! Levon would shout out to the Greek relative famed for her cooking. “You know the Armenians taught the Greeks how to cook, Stella!”

There was a stretch of time when my grandfather would say that his people came from “rocks and sand.” Given to dramatics, he’d say that his homeland had no name. When I’d insist that every place is somewhere and every place has a name, “Asia Minor” would be his reluctant reply, with a waving of hands, affecting a forced guess. After Armenia gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, with great fervor, he and his brothers would cheer, Getseh Hayastan! (“Long live Armenia!”).

As the years passed, Getseh Hayastan! would be proclaimed with renewed zest and novelty, as happens with the shortening of short-term memory. Each repetition of Getseh Hayastan! would be exclaimed with all the vigor and volume of one with diminished hearing, loud enough to wake the dead. And maybe that was the point. There were, after all, so many dead.

Aram writes in Last Rites, “Armenians, understandably, love and adore [William] Saroyan as their poet, their spokesman, their champion in a world that has been full of terror and depravity…” He’s a national treasure, and through his writing, has brought recognition to Armenians as much as to himself. For a people “subject to genocide, both physically and spiritually,” Saroyan’s stories are redemptive (Saroyan, 1982). Accordingly, Levon was a Saroyan loyalist, and though details faded over time, we loved his recount of the Chinese dinner story as much as he loved recounting.

“The Armenian and the Armenian,” an essay from William Saroyan’s second book, Inhale & Exhale (1936), speaks to the Armenian Genocide in which 1.5 million+ Armenians were killed. Apparently, a first writing of the essay was in somewhat coarser language than the popularized G-rated version. Venerated on posters and cards, the latter reads like a proclamation of Armenian solidarity, and has served to further immortalize William Saroyan as Armenia’s and Fresno’s favorite son.

I should like to see any power of the world destroy this race, this small tribe of unimportant people, whose wars have all been fought and lost, whose structures have crumbled, literature is unread, music is unheard, and prayers are no more answered. Go ahead, destroy Armenia. See if you can do it. Send them into the desert without bread or water. Burn their homes and churches. Then see if they will not laugh, sing and pray again. For when two of them meet anywhere in the world, see if they will not create a New Armenia.

Armenians the world over know these lines like a prayer. It was no surprise then that my grandfather kept a small photocopy stashed in the top drawer of his office desk where he showed up every day at 7:00 am sharp, almost to the end. For a season, I had a job nearby that allowed for early morning visits, during which he’d often pull out the old photocopy, fraying at the folds, as if fulfilling his promise to Old Man Krikor. It was only fitting that it should be his swan song, and that I would read it at his funeral in 2003.

During the funeral weekend, a woman from the community pulled me aside. She confided that her then-teenage daughter had been adopted from an Armenian orphanage in Beirut, and that my grandfather had been instrumental in the process. What’s more, she said, her family wasn’t the only one he’d helped with adoptions. I tried to ascertain more information, to no avail, alas. Aram describes his father as an enigma, one with stamina, talent, and elements of genius (Saroyan, 1982). Ditto for Levon.

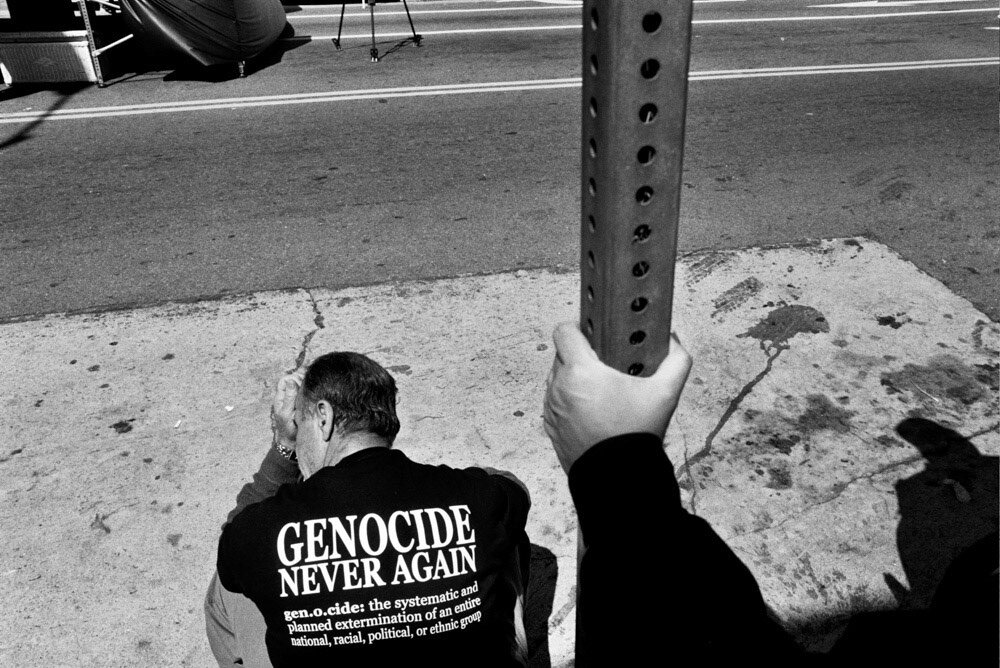

The torch was passed from Saroyan to Saroyan, from Genocide survivors to their descendants, from one generation of storytellers to the next. We are wielders of truth of a genocide denied, keepers of faith in a new Armenia, and as Der Hayr Mesrop Ash of San Francisco’s St. John Armenian Church confers, we have a sacred contract to fulfill. We are descendants of Anatolia, of old Constantinopolis, of Smyrna, of the Levant and Mediterranean Sea, daughters and sons of the sun and sea and rocks and sand, and we are two Armenians exponentially.

Riffing off another favorite son of Armenia, G. I. Gurdjieff (~1870-1949), these “meetings with remarkable men” hold us to the promise to never to forget, and never again, and Getseh Hayastan!