We all remember the cataclysmic wildfires in Australia and California, but our attention was overtaken by the pandemic and US presidential election. Yet, according to data released by the Copernicus Climate Change Service, globally 2020 was on par with the warmest year ever recorded (2016), marking the end of the warmest decade on record. Johan Rockström, director of The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) said that while it is not about record heat in any given year, “we are looking back on an alarmingly warm decade with an alarming amount of extreme weather events […] — never before in the history of human civilization have we had such warming.” Rockström said the trend could only be stopped by quickly reducing CO2 emissions. “We can make the reduction, but we really need to start now.” (Clean Energy Wire)

Iason Athanasiadis

The streets of Tunis were deadly quiet on New Year’s Eve; the streetlights’ diffused orange only slightly pushed back the darkness. My partner and I stole along deserted lanes, slipping through the medina on our way to an early 19th century building in the Tunisian capital’s walled inner city, where friends celebrated the changing of the year.

I avoided crowds even before the pandemic, and usually don’t celebrate the New Year, preferring not to inflict my winter melancholy on others. But this year felt different: the usual manufactured cheer was absent, and the desolate city’s facades and polished flagstones coaxed us outside.

Online, conventional wisdom had it that 2020 had been a terrible year. Scrolling through fervent digital supplications for a return to normality in 2021, I wondered what very different things that might mean to each of us. Perhaps most of us alive today can’t say we’ve experienced what could honestly be called normality, at least in climate terms. And we’ve certainly not witnessed authentic Nature, unmolded to human needs by industrial society, for at least a century (or three, depending on where you live).

But in 2020 we came closer to Nature during the first days of quarantine. With humans sheltering inside, birds appeared in larger numbers over the cities, and a succession of shimmeringly-clear days dawned. Pollution clouds cleared from cities across the world. We became unexpected recipients of a month of Sundays, and began sharing videos of dolphins frolicking in the Bosporus’s suddenly clean waters or wolves and deer cheekily traipsing up main streets and through front gardens.

And yet, all of last March’s wonder at how quickly and brilliantly Nature can reconstitute itself, had apparently been forgotten by New Year’s Eve as people clamored for a personally better 2021. It felt a little … scatter-brained, for want of a terser adjective.

Of course, there was nothing fun about a year of home confinement, reduced income and fearing for oneself and loved ones, especially while tax-evading, globe-trotting elites continued roaming unaccountably.

In Greece, where I live, the right-wing government turned the crisis into an opportunity, hiring new police recruits, buying equipment and closing arms deals instead of investing in doctors, nurses and the health sector. Its legislators took advantage of the cleared streets and a population hooked to daily pandemic briefings to push through anti-worker legislation and finally overcome local opposition to environmentally-destructive alternative energy.

Ships deposited parts in harbors that had, until recently, been blockaded by locals, and soon landscape-scarring wind-turbines balanced upon enormous concrete bases cropped up all along newly-carved roads. Ecological destruction was being carried out in the name of saving the environment, in pursuit of the chimera that we can maintain our way of life by simply switching to green energy.

Just like my friends, I wasn’t looking forward to seeing this year repeated, but it seemed unavoidable as long as we continued to perceive things in individualistic and isolated ways, limiting ourselves to the innocent hope that our little world might return to what it once was. The irony of wanting back a way of life that had driven climate change, and contributed to the chopped-down forests and intensive livestock farming that incubated the pandemic, apparently elided us.

2020 was not a departure, but a logical continuation of everything preceding it. Treating it as a fluke event and expressing a sense of loss about the polluting, consumeristic normality in which we, as high-income, energy-guzzling First Worlders were paused from participating, was dishonest. Perhaps it would have been better to anticipate getting “our lives” back only after we’d changed the circumstances that got us here in the first place.

As I walked through the streets of Tunis, I thought about some of the uplifting things that happened in 2020: CO2 output had dipped by 9% in its first half, a huge reduction compared even to the 2008 economic crisis. And humanity also proved it was capable of taking urgent and decisive action to save the climate, even if the results we were seeing were just unintended side-effects of measures adopted for a more anthropocentric purpose: protecting us from the virus.

The lockdown also gave us the gift of time, the most valuable commodity in an attention-clamouring century. As the frantic roundabout of commutes and social, academic and sports events came to a halt, reading a book reemerged as a possibility. It was a magic opportunity for self-improvement, and a test-drive for how a life lived under a Universal Basic Income (UBI) regime might feel.

Computers and robots are increasingly running factories, hotels, and vehicles, but no one has addressed what will happen to all the unemployed humans now that it has been some generations since we live to work instead of working to live. Putting everyone on UBI could deter social unrest, but it could also evolve into a disciplining mechanism akin to the system of reward-based social control that China adopted. This is a nightmare scenario, but so is business-as-usual on a slowly-baking planet.

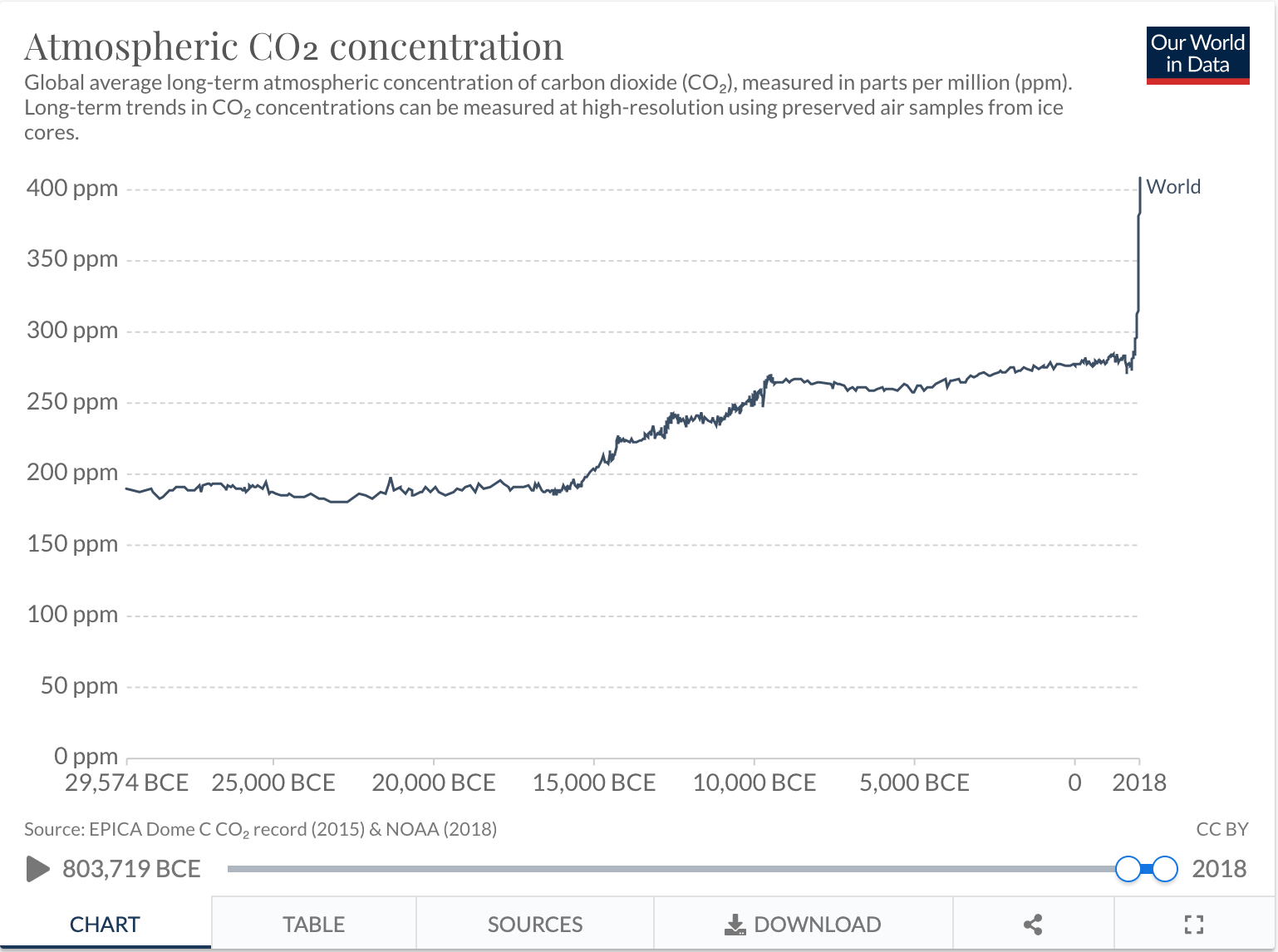

The post-Second World War consensus that consumerism-fueled 3% annual growth could avert a repeat of the chaos has ended. Environmentalism wasn’t even a fad at the time, so the consequences of unbridled industrial growth on the planet were ignored. CO2 emissions detonated, resulting in historically-unprecedented CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere, which peaked in 2016 when we crossed the 400ppm (parts per mission). That year, we churned another 36 billion cubic tons of CO2 into the atmosphere. And since there’s a lag before emissions make their presence felt, the ppms just kept on rising (they’re around 410ppm now), even despite 2020’s unprecedented reduction. But there is now already enough CO2 in the atmosphere to ensure we push past 2 degrees of climate warming—and in 2021, we’ll also exceed 417ppm, even though in 2019 UN Secretary-General António Gutteres called 410ppm “an unbreakable tipping point.”

This all resulted in 2020 being the hottest year on record for the planet, almost 1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial times, and perilously close to the 1.5 degree limit set by the Paris climate agreement. But even though our dystopian climate catastrophe is no longer in the future but part of our lived reality, the Chinese economy went back to pumping out pollution after overcoming its pandemic, and some people remain anxious about going back to an imagined normality.

Well, at least the US under President Joe Biden will rejoin the Paris Agreement. But will the US still insist on the Pentagon, the world’s single largest institutional consumer of petroleum whose annual emissions rank it 55th in the world, remain exempt from oversight and reductions in emissions? The fact is that the US military is as big a polluter as 140 countries.

In Tunis, I was still thinking such thoughts as we counted down to the New Year. We kissed and wished each other all good things for the year. A few minutes later I brushed away a mosquito, incredulous to be seeing one in January. It was 2021, and I realized that my fervent wish was to never go back to normality.