Samia Errazzouki

Morocco’s historic performance in the 2022 World Cup has attracted worldwide attention. As the first African and Arab country to advance this far in the tournament, countless people from across the globe have lifted the Moroccan flag in support and admiration. At the same time, while Morocco has become a source of joy and elation for many, there are those of us who celebrate with muted cheers so as not to lose sight of the struggle against the regime’s authoritarian regression. From prison to exile, we shed both tears of joy and tears of longing for a country we deeply love but which at times does not love us back.

My Moroccan parents fled their homeland in the 1980s during the height of what is known as the “Years of Lead” — a period marred by political repression, economic hardship, and human rights abuses. They emigrated to DC and started off as busboys just a few blocks from Capitol Hill, slowly working their way up. Within a few years, they became US citizens and settled into their lives as members of the DC suburban middle class. It was then that I came into the picture, probably ruining all the fun in the process. It was in the suburbs of DC where I spent the first 25 years of my life, sprinkled with annual summer trips to Morocco.

Fast forward to 2011: following the mobilization of protests during the Arab Spring, I, like many born into the Arab diaspora all over the world, wanted nothing more than to do my part in contributing to this meaningful change. And so, the day after graduating with my masters degree in Arab Studies from Georgetown University, I booked a one-way ticket to Morocco, where I began working as a stringer for the Associated Press, and then as a correspondent with Reuters.

As required for all those who report for foreign and international news outlets in Morocco, I filed my request for press credentials with the Ministry of Communications. While waiting, I was free to work — so long as my stories steered away from crossing any of the major red lines in Morocco, namely challenging Morocco’s claims to the Western Sahara and criticizing the monarchy. Eager to begin reporting, I hit the ground running. I covered a range of stories, from the government’s efforts to combat climate change to peaceful protests calling for more hospitals and improved infrastructure. Among these reports I covered the violent dispersal of protests and shipments of phosphates being held at international ports. I was also the first journalist to whom former Prime Minister Abdelilah Benkirane spoke the night that King Mohammed VI replaced him after his failure to form a coalition.

Every now and then, I would reach out to the ministry and ask about the status of my press credentials: “soon” turned into “we’re working on it,” and eventually to no responses. This would mark the beginning of a series of contentious encounters with officials.

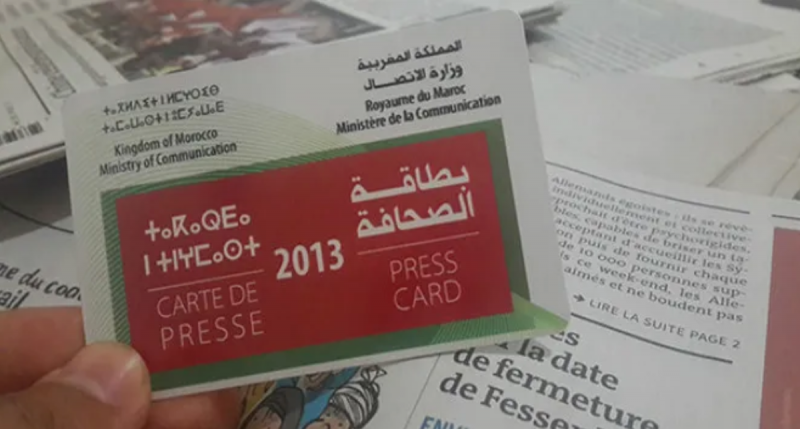

Without a press card, journalists cannot attend certain press conferences or receive statements from the Ministry of Interior — a significant obstacle to doing one’s work as a reporter. On several occasions, I approached officials during press events to ask what was stalling my application for credentials. Eventually, a high-ranking government official informed me that the delay was due to visits I had made to the Western Saharan refugee camps in southern Algeria, prior to my move to Morocco. Finally, just before the 2016 elections, I was told my press card was ready.

At the Ministry of Communications, I was escorted to the office of a bureaucrat who held my press card in his hand and proceeded to lecture me about the importance of being a patriotic Moroccan. When he handed me my credentials, he sternly stated: “Above all else, remember, you are Moroccan before you are a journalist.” The next day, my name appeared on the front page and above the fold of a major newspaper in a blurb that disclosed I had received my press card “despite my connections to separatists.” This same bureaucrat had also summoned a colleague of mine to scold him over a story he had written, telling him, “Just watch out, you know, accidents happen sometimes.”

After that, things began to go downhill. On several occasions, the concierge of my apartment building informed me that plainclothes officers questioned him about my movements and visitors. Clicks in the background of phone calls became common place, and in a few instances, I heard some of my previous phone conversations replayed as I attempted to make calls. While on assignment, prolonged questioning at security checkpoints became the norm. I was also being followed by unmarked cars. I was roughed up by police while covering demonstrations, even after presenting my press card — in one case, a police officer even accused me of forging my press card.

Eventually my dreams of living in Morocco were cut short as I began to realize that the “Years of Lead” were no longer a chapter of the past, but rather, a resurging reality of the present. Other journalists and friends of mine were facing arrest, deportation, harassment, and threats. I suspected that it was only a matter of time before I too would become a target. With a heavy heart, I packed my bags and returned to the US in 2017. Just a few days after I got back, I spoke about the deteriorating situation in Morocco during a conference in Washington — among the speakers in the panel that preceded mine was Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Like Khashoggi and other journalists who fled their homelands out of concern for their safety, I learned that leaving my life as a journalist in Morocco would not put an end to my trials and tribulations. To this day, I continue to face a relentless and coordinated harassment campaign online — from death threats on Twitter to defamatory articles on publications subsidized by the state. This reality has sowed a corrosive anxiety that has become part of my daily life.

But this treatment pales in comparison to what many of my colleagues have faced. For example, one publication with close ties to the security forces has ruthlessly engaged in the character assassination of a number of prominent human rights defenders and journalists. Just last year, this publication posted a video of a human rights lawyer and former government minister undressing in a hotel room. Days before the arrest of journalist Omar Radi, this same publication wrote that he would eat boulfaf in prison, a traditional Moroccan dish served during the holiday of Eid al-Adha. Sure enough, he was arrested on July 29, 2020, just a couple of days before the holiday.

Today, it is safe to say that there is no independent media in Morocco. Some of the country’s brightest and most skilled journalists sit in jail, have been exiled, or pressured into silence. What we are witnessing in Morocco is the culmination of years of repression that, in some ways, are worse than the “Years of Lead.” Whereas journalists and dissidents commonly faced political charges in the ‘70s and ‘80s, today they are charged with crimes of a sexual and moral nature. The two latest examples of these cases have been journalists Soulaiman Raissouni and Omar Radi. A number of rights groups and observers, including at the US State Department, have pointed out fundamental violations of due process in their trials.

Today, the Moroccan state has weaponized the #MeToo movement as a way to selectively silence critics rather than treat all sexual assault allegations equally. While Raissouni sat in isolated pretrial detention for over a year before his conviction, just a few years prior, King Mohammed VI personally paid for the legal fees of a Moroccan pop star who still faces a number of rape charges and allegations. Ultimately, this sends a worrying message to all victims and survivors of sexual assault in Morocco, myself included.

One particularly shocking example is the case of Hajar Raissouni, a journalist at Akhbar Al-Yaoum Daily who in 2019, convicted for having premarital sex and an abortion, was sentenced to a year in prison, although the medical evidence proved otherwise. The court sentenced her fiancé to a year in prison and her doctor to two years. Raissouni denounced her case as political because she works for an independent newspaper that has been critical of authorities.

In February 2018, when authorities arrested editor Taoufik Bouachrine over charges of rape and human trafficking, several women came forward claiming that police had falsified their eyewitness testimonies to characterize them as rape victims. One of those women, Afaf Bernani was later sentenced to six months in prison for perjury and defamation, prompting her to seek exile in Tunisia. She wrote about her ordeal in an op-ed in the Washington Post.

It was these troubling inconsistencies that motivated Hajar Afaf and myself to establish Khmissa, an NGO that takes an intersectional approach to feminism. We founded our organization on the idea that women’s rights are inextricably linked to press freedom, freedom of expression, individual liberties, and the need to free political prisoners in Morocco.

Over the past year, the situation in Morocco has continued to deteriorate. Human rights defenders Saida El Alami and Rida Benotmane have been arrested and charged for speech-related crimes over posts they made on social media. Their cases are among the many victims of what Human Rights Watch has characterized as “Morocco’s playbook to crush dissent.”

Growing up in the suburbs of Washington DC, my character and convictions have always been heavily steeped in the American values of freedom of expression and human rights. What drives my work and what has brought me where I am today is the simple vision that one day, Moroccans too can share the gifts of these values with which I grew up. Where else could someone like me, an American citizen, speak before a congressional commission named in the honor of the late honorable Tom Lantos — a Hungarian-born Holocaust survivor — to advocate for freedom of expression and human rights in Morocco? As a Moroccan American, this is my humble contribution in honoring, preserving, and advancing the alliance, national security, stability, and welfare of two nations that I am proud to call home.

Samia Errazzouki gave an earlier version of this essay as a talk at the Human Rights Commission named for Tom Lantos last year.